A counter statement to Camus, an Iranian director explores the intersection of Arabic and European cultures

The Algerian man, shot by Meursault in Albert Camus’ 1942 philosophical novel, The Stranger went unnamed, his history undocumented. His purpose for Camus was purely philosophical, his dismissal symptomatic of the prevailing colonialism of the time. More than seventy years later, Algerian journalist, Kamel Daoud, switched the perspective to that of the victim, giving him a name and a story in his novel, The Meursault Investigation. A move that proved so controversial that it led to fierce academic debate in Europe and a fatwa in Algeria.

Now, Iranian director, Amir Reza Koohestani, has created a play at Münchner Kammerspiele, drawing on both books in a bid to reach a cross-cultural understanding of “general principles of suppression, re-appropriation and self-assertion.” How can we find a way to live together? With a multi-national cast speaking Farsi, Arabic & German, also surtitled in English and German. As the Kammerspiele’s brochure observes: “a multi-perspective language panorama”…

An Arabic woman, a mother, rushes onto the stage from the auditorium clutching a framed photograph asking repeatedly: “My son. Has anyone seen my son?” Pleading in Arabic, apologising continually for not speaking German, harking back to those restrictive colonial days. Or perhaps forward, pointing up a shared humanity if only we could cross this cultural chasm.

Heavy sandbags are dragged back and forth across a rug-covered stage disgorging themselves until all is covered in a fine coating of sand. This is Algeria, then and now. A head thrusts up through the floor. The head of an old man, who introduces himself by reference to the little boy attending the mosque at the side of the stage “That’s me. Harun.” A middle-aged man comes on stage. “You are me but younger” says the head. “No” replies the other “I am you, but older.” Three Haruns. None of them have a brother. Not since Camus.

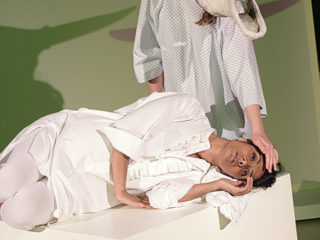

A gunshot. In flashback, to that key moment in The Stranger. A man, now identified as Musa, brother of Harun, falls to the ground. “Du hast mir geschossen [you have shot me]” says the disbelieving Musa, over and over and over as Meursault continues to fire. Five times Meursault shoots him. His defence? “You had a knife. The sun on the blade blinded me.” Middle Harun walks over to his brother and cuts out the carpet around his body to show their mother the shape of her dead son, so she can try to complete, to start the clock of her life ticking again. The body is buried, hurriedly, shovelfuls of sand flying everywhere. Splashes of water rise up as he’s thrown into the bottomless grave, the sea folding around him, his sinking body beautiful in its watery grace.

The bullet is always coming for you. Excruciating in its slowness. Your mother doesn’t age, she can’t move on – time has stopped for her. But she won’t let it move for you either. You can’t, won’t, take revenge. Old Harun has despaired – renounced God and taken to drink. “God is a question, not an answer. I didn’t waste another moment on God after this.”

Twenty years pass and nothing happens. Except that it does. The war of Algerian Independence happens – a change in everybody’s fortunes, their identity and social value. A chance to shoot at a random Frenchman. Vengeance at last but Harun still ends up in prison at the hands of his own countrymen. It’s a no-win. He’s killed someone in an act of revenge, but it’s taken him too long. Now the new authorities want to kill him. “No” he says, “my mother has only one son left.” Not good enough. “She’s a storyteller, I am her son. If you kill the last remaining son of a storyteller who’s the mother of a martyr, she will tell everybody, and they will listen. And the martyr will become a martyr.” They set him free: “Go then, live, burdened with your grief, your guilt.”

And so we move on, cameras intensifying the action, a dual perspective of talking heads, facing inwards intent on each other in life, but on screen, facing out at us, their audience. all trying to find a way forward across time, across perspectives.

Arabic. European. Two cultures trying to speak across the divide.

Photo credits

Homepage : Production picture detail. Original photo © Judith Buss

Main photo : Production picture. Photo © Judith Buss

(Photos courtesy of Münchner Kammerspiele)

24 May 2018:

Der Fall Meursault : Eine Gegendarstellung

Münchner Kammerspiele, Munich

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.